This post is a quick and drafty response to a change of plans: the Live with Michelle Strauss on personhood is postponed! Updates to follow.

Nevertheless, I hope you stay with me for a special edition of my Hot Topics-series. Last week, I haven’t been to my regular sauna but to a very hot Hamburg (temperatures soared, up to 32°) — and I am just so keen to share some freshly baked musings on:

Talking to strangers and as a stranger about the current political landscape in Germany

Acknowledging the human in the more-than-human

I am writing this on a long train ride back to the UK. The train keeps interrupting its journey, is running late — for various reasons. So does my train of thoughts.

My seat number is 88. As a German-born person with migration background, I instinctively recoil when I see that number. Or perhaps that response is produced by the rest-self of the suburban punk I was, who learnt, as a teenager, about the long history of secret political symbolism in Germany. You see, 88 can be read as HH, because H is the 8th letter in our alphabet. And so HH can stand for “Heil Hitler”, which is something you are by law not allowed to say in Germany. I think it’s Aristotle who said that the law comes in where friendship and a shared culture among citizens is not enough.

Sprächen Sie überhaubbt Doitsch? I like language. I like to play with language. It has been like that ever since I was given language, and I vividly remember my excitement when I found my first “Umlaut” on a cardboard box in our yard: ÄPFEL VOM BODENSEE — way before school. Because I like playing with language, I have been invited to join the first Nature Writing Festival in the German language, which took place last week in the city where I was born: Hamburg.

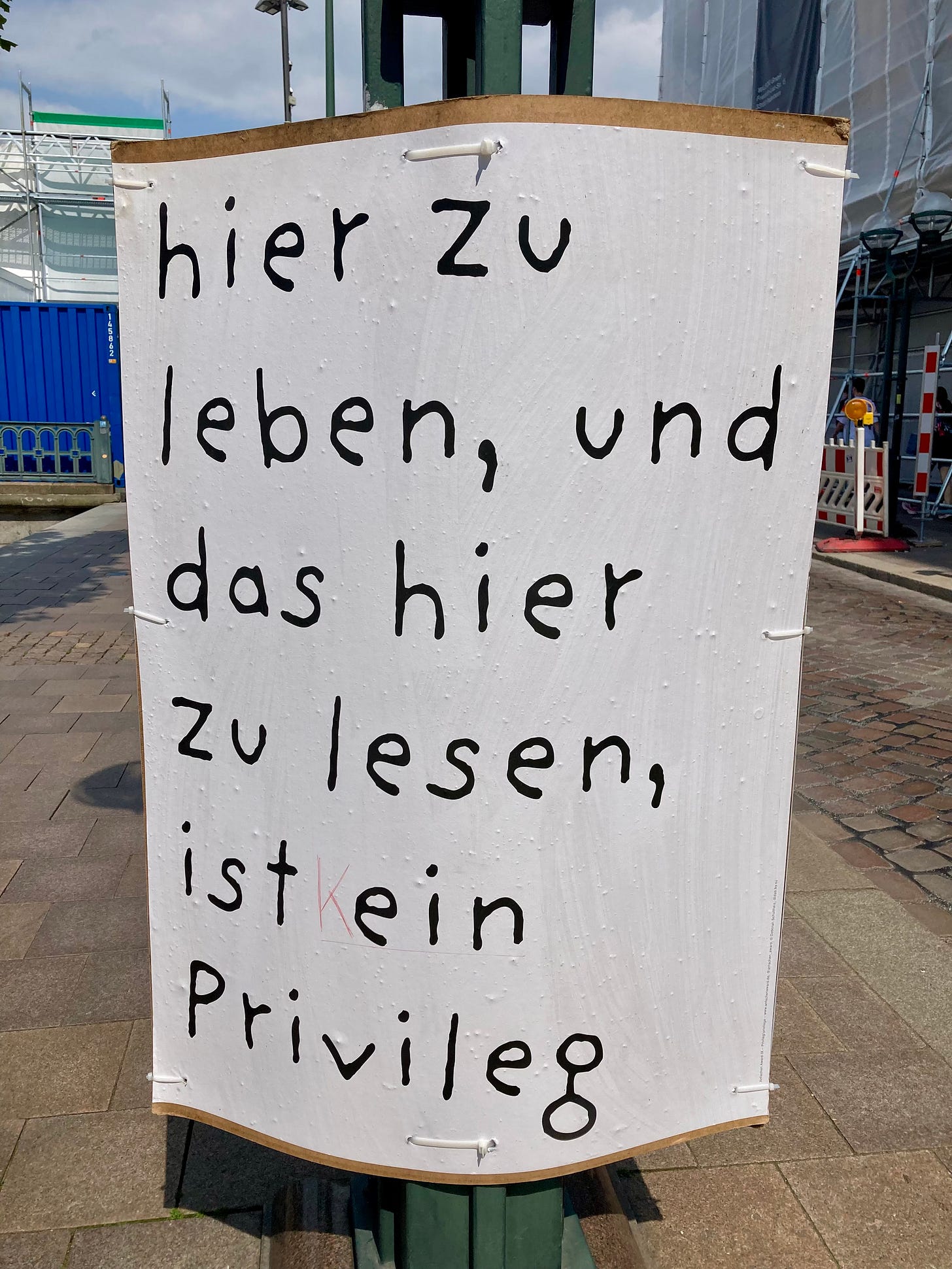

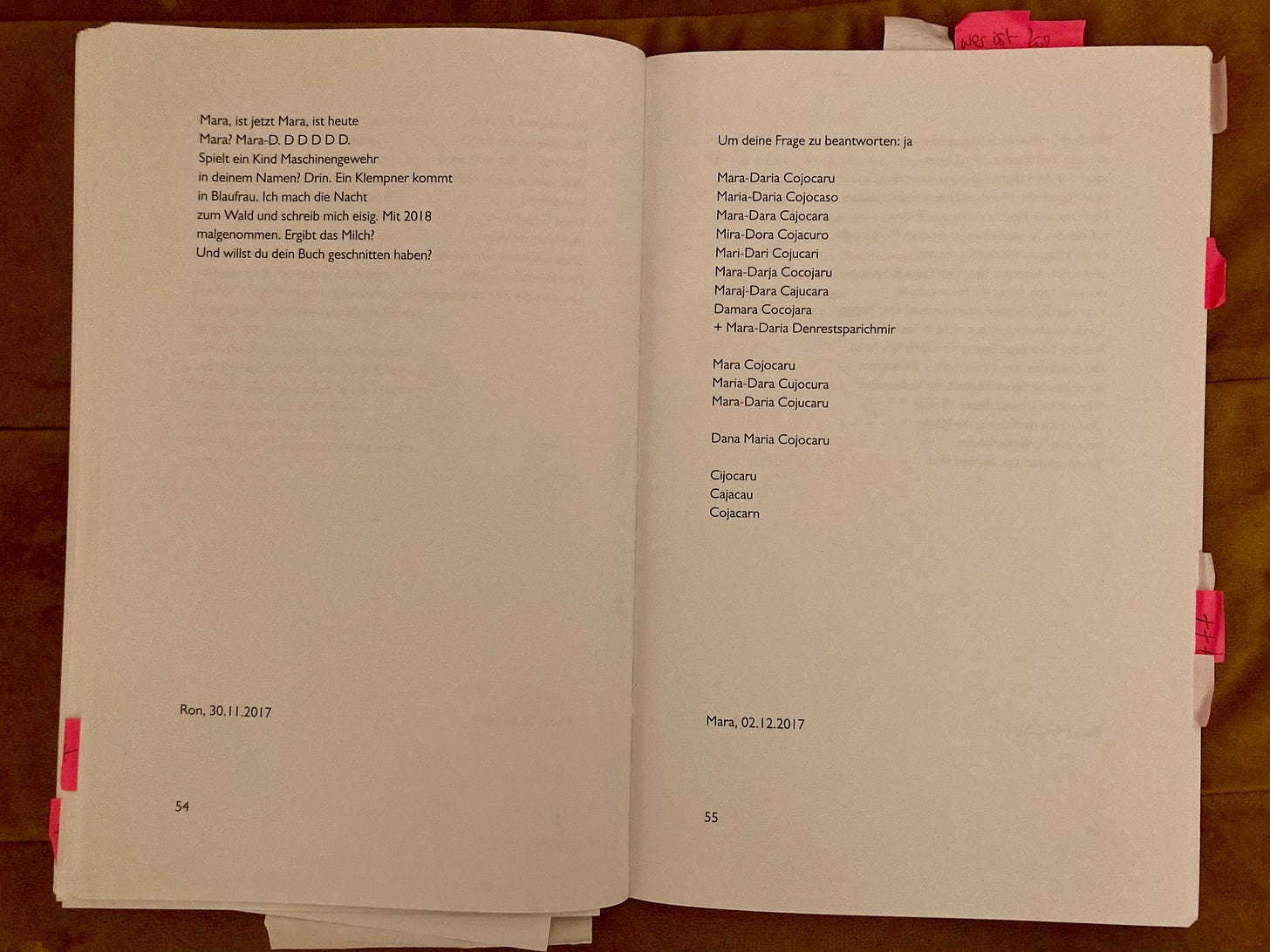

My mother tongue is German. Yet my Romanian name often caused irritation. I once applied for a job and I would have had to answer the phone. I was asked whether I was actually fluent in German. By that time, I had not only won a backpack for my poetry in elementary school and was taking German literature as main subject in high school — I had also already spoken about five minutes with the person on the phone … “Still, you would have to give a different name when you answer the phone!” I didn’t get that job. I became a poet and philosopher.

The poet and philosopher who currently reside in the UK leave the train in Hamburg and the little punk is happily swinging between their hands. The philosopher stops because her eyes spy a tattoo on a muscular upper arm. Some symbol she has not seen before, and underneath a date: 27.8.1933. The poet is keen to get to the hotel. But the punk agrees: This needs investigation. Why would anybody want a date from that year under their skin? Google helps. Three possibilities.

The Jüdisches Museum in Berlin lists a marriage contract between Heinz Gottschalk and Liselott Feilchenfeld for the day. The wedding took place against the backdrop of rising antisemitism in Germany after Hitler had been appointed as Chancellor.

Wikipedia tells me that Louisiana Senator Huey Long ended up in a brawl after he is said to have pissed on the man in the neighbouring urinal and received a black eye.

The Hitler Archive tells me that Hitler met that day with Hindenburg and Göring to commemorate a horrific battle that took place during the first month of World War I.

To me, the aesthetics of the tattoo make it unlikely that that sporty German chap in 2025 — who looks nothing like the chubby, stinking Neo-nazis of my suburban youth — is commemorating a Jewish wedding. It’s hard to say what he thinks of pissing on other people. Perhaps one of his relatives was born or died that day. Perhaps! But perhaps he is just one of the increasing number of people who think that some humans are inferior to others. Unter-Menschen. Not humans among humans. Certainly not humans as animals among other animals. But that lame old story that is often connected with the subjugation of other animals, too. Lame, but dangerous nevertheless.

People push past, usher us on. These days, I don’t regularly spend time among people. I work from home, I teach online, I travel for some events but not very many. My work with and for other animals has made me sensitive to body language and even odours. It frankly flashes me to be “unter Menschen” for this nature writing event.

I have that new thing where I ask strangers to take pictures of me somewhere for me, because, if I am honest, I like having memories! But I never liked selfies. This was the fourth time I have asked a complete stranger to do this for me. I loved the colours, the hotel, the rooftop terrace (complete with sauna), and I just started to like these little awkward interactions, too. These tickles of spontaneity, the process of scanning people for the ones of whom you think you can ask a favour, perhaps a bit like an Indian streetie. I wasn’t prepared for what followed this time, though. I considered the interaction over, but the brief poking of the bubble of the self that has to keep it all in and all to itself had motivated the person who had taken my picture for me to give me … a pretty full picture of their life.

The poet, philosopher and punk were astonished — had they missed that a therapist had joined them? Increasingly, when I am unter Menschen, people talk to me about things they feel they can’t but have to talk about. Whether that is a Syrian refugee who sadly feels he needs to assure me that his name comes in a Christian version, too, or this business man selling security cameras for trains. I pay attention to his words which move like reeds in a twisty breeze:

He is unhappy with the desolate condition of the German army.

He detests the AfD.

He thinks complete surveillance of public spaces is a good thing so that people follow the norms.

He despairs over the fact that his ex-wife did not meet their child with the love and understanding they needed when coming out as a trans-woman.

He doesn’t read books.

He plays the violin. And. so. on

The device that surveys his blood sugar levels ends our conversation. I sit with it. I don’t know what to say or think. The poet has a headache. The philosopher is running late for the first event.

Humans are political animals. Other animals are political animals, too. That is something already Aristotle knew. Aristotle thought that humans are animals endowed with speech, and other animals are not. Which is why he thought humans were special political animals in that they could debate about the good life. Now that we know that other animals have language and conceptions of the good life, too, isn’t it just a little curious that we increasingly fail to engage in meaningful political conversations about the good life with fellow humans?

I am chairing an event with Lea Schneider, a German poet who is working on a book on human relations with the more-than-human. I like Lea. She suggests that we should adopt a much broader conception of what a person is — every surprising body. I disagree. Not in principle. But details matter here, in a room packed with people who have come to listen to us on a hot summer evening. I welcome the increasing interest in the more-than-human. Persons were always more-than-human. Think angels. Think corporations. But then think Happy and how hard it is to fight her case. How come, then, that people seem so eager to ascribe personhood to rivers, and seas, the planet as such? I am skeptical and sensitive to the politically conservative undertones in these and similar arguments. I feel this lets anthropocentrism in through the back door — and centre stage. Lea disagrees, which is great. It’s a different anthropos. We debate. Somebody in the audience disagrees. In principle. I help Lea defend her general point.

At night, I meet another German poet who says: “The other day, my neighbours, who used to be Nazis and today are just right-wing, helped me when Nazis cut my tyres — das geht dann doch zu weit.” I repeat: “Your neighbours who used to be Nazis and today are only right-wing?” She nods. She has kind, sparkly eyes. She says she likes her neighbours. She also says you can only make progress on a political issue with people if you like them. I think Aristotle would like her. I like her, too.

I notice that I like everybody I speak to. The person who disagrees with me. The person who agrees. The person who first agrees and then disagrees. The person with the puzzled face. The person with tears in the eyes. The person who has said and done things I strongly disagree with. The person who makes me feel insecure. The person who falls silent with me and it’s okay.

That is odd, says the philosopher. You talk a lot, says the poet. You’re alright — the shrunk punk.

As I get up, my eyes fall on hoodies, caps, sporting words like: Nationalgarde, Lonsdale. The people speak Spanish. I hope I get to catch my next train.