“I don’t know much, but / I know I am here / So let’s take a look around”

Interview with Will Strand aka Gecko and Viola Karsten

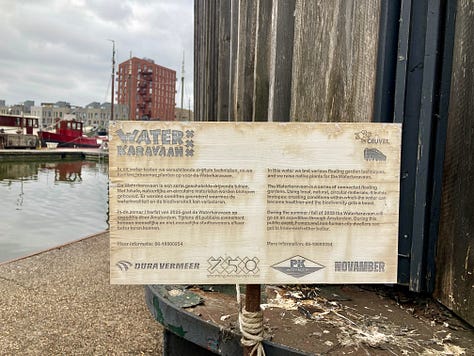

In this post, singer-storyteller Gecko and Goethe Institute cultural programme manager Viola help me explore De Ceuvel, our Amsterdam site for “Philosophy in the Wild: Finding Hope in Mixed Communities”. De Ceuvel is a zoöp – and if you don’t know what that is, don’t worry, learning about this concept is exactly the point.

‘Zoöp’ is short for zoöperation, playing on the Greek word for life ‘zōḗ’. It is an aspirational term for a novel organisational model and learning process that aims to incorporate non-human perspectives into decision making concerning regenerative practice. In a zoöp, the interests of the ecosystems in which the organisation is situated and participates are actively represented by a speaker for the living.

To me, this sounds like a natural conclusion of Mary Midgley’s book Animals and Why They Matter, promising to address some of the perennial tensions between social and ecological claims in our mixed communities.

Will, I want to start with you because when I visited De Ceuvel in May, I stumbled into your concert on one of the boats, the one that is home to Amsterdam Music project, and you struck me as a “speaker for the living” in your own right. The title of our interview is from a song on your new album, “Take a Look Around”, in which you playfully celebrate much of what we know and don’t know about evolution. With “Philosophy in the Wild. Finding Hope in Mixed Communities” we aim to transform human relations with wild living animals specifically, and another one of the songs you played that night made me think I just must ask you whether you want to play along – the song is called “Soaring”. Could you share a bit of the story behind it?

Sure. It’s a genuine childhood memory of mine mixed with an imaginative account of me as an old man in a care home. I was a city child, but we spent summers at my grandparents’ place in Norfolk. One afternoon, I was running around in the woods by myself and stumbled across this pheasant – I didn’t know what it was and just thought I had made an amazing discovery, ran home to share, and the adults were like: “Yeah, that’s a pheasant”. That bit is real. Now, care homes can be miserable places and I know about some such homes where animals make a huge difference for the people. And I just thought of my imaginary grandchild doing this spectacular thing that I describe in the song, creating that uplifting, celebratory moment, liberating pheasants, who had been designated to be shot, in the process.

In that song, you briefly mention “your dad”. You told me that your actual dad has lovely memories of Mary Midgley because he studied with her. She didn’t just offer biscuits and philosophy but even … pizza?

Yes – and Monty Python! I asked my dad about it – and he said:

“Mary’s seminars were lively and never dull. Mary would listen intently to the halting contributions from us students; leaning precariously backwards in her chair, a cup of coffee in her hand and her eyes closed. Her responses seemed always to manage to make our efforts seem better than they were, so effortlessly did she make the connection with the text under consideration. We were spellbound both by her clarity of thought and her ability to suddenly lurch back to the horizontal, mostly without spilling her coffee, and launch another train of ideas. She was intense but kind and able to draw in the shyest of us and make us feel worthwhile.

She, with her husband Geoff – also a philosopher in the department – invited us regularly to their home ‘to watch Monty P’. This being in the pre-digital early ‘70s when students didn’t have screens in their room. She would order pizza or curry for the dozen of us who accepted the invitation. So generous. I have a vivid memory of both Mary and Geoff laughing uproariously at the Philosophers’ song sung by Idle, Palin et al.

I have to say I was an undistinguished student but after I graduated, Mary nonetheless responded to a request from an employer with a reference for me that was glowing and perceptive, so illustrative of her depth of understanding of people as well as ideas.”

Will, you sometimes talk about things people don’t want to hear about – animal experimentation, farmed animals. A speaker for the living must be good with people, too – chapeau, I admire your approach. I feel Midgley would like it, too, because you really tickle the “inner child” she mentions, those remnants from when we didn’t take ourselves and our human concerns all that seriously. How do you do that? And do you have feelings about zoöps in general or De Ceuvel in particular as inspirational places of learning to live and work differently?

I love playing shows in unusual spaces so when it was put to me that I needed to come and play on a boat in Amsterdam I was immediately amenable to the idea. That was quite a few years back and since then I’ve returned to play shows at De Ceuvel maybe three or four times. The area feels like a creative oasis – and it’s surprising that it’s so near to central Amsterdam. From those visits I knew a little about the fact that it was a regenerative project revitalising an old shipyard. The concept of the zoöp is however a new one to me. I really like the idea of a speaker for the living and agree it does seem to chime with a lot of what I seem to be doing with my songs.

I gravitate towards writing a fair amount of songs in character and a lifelong affinity with animals seems to guide a fair amount of those character songs. And this sort of storytelling can be a way to approach difficult topics without people immediately shutting off and putting up their guard. For example, my song about The Tamworth Two pigs (a true story from the ‘90s in which a pair of pigs escaped slaughter) takes the guise of a runaway ballad, something you could imagine in the Great American songbook — only this time, it happens to be about pigs. I think you can’t help but empathise with this brave duo – it plays on emotional beats rather than if I just sang that ‘factory farming is bad’ etc.

I think trying to reignite people’s inner child is also essential – trying to break down the barriers and baggage that adult life can easily suffocate us with. I also think writing from animals’ point of view can be useful because you can be scathing of humanity’s impact without the whataboutism that can easily be thrown back at you when you make these points as a human being. Me and my brother made a whole audio drama musical with this in mind, called The Flock, in which a group of birds fight back against human destruction.

Thank you! I loved that, perhaps especially the parting song of the Wisest Bird. Now, over to Viola. You have just seen through the residency of German sculptor Fabian Schäfer at De Ceuvel, which was part of a EUNIC funded project, Zoöp Connections. New Networks for the Living. What are the most important findings?

We are still processing! During the residency, Fabian became particularly interested in what he calls “Concrete Ecologies” — life within urban infrastructures. Places we usually think of as "unnatural" are in fact active environments, where lifeforms like lichens exist in the tension between decay and renewal.

One striking experience during the residency showed just how ecological transformation is a collaborative process that is never really finished. A large tree fell right outside Fabian’s window. As a trained tree worker, he helped the De Ceuvel team to cut and examine it — and the trees nearby. Together with Thijs de Zeuw, De Ceuvel’s "Speaker for the Living", Fabian looked closely at the tree. While the lower trunk was almost bare, the top was full of lichens — a sign of a healthy, living ecosystem.

The lack of lichens lower down reflects the challenges De Ceuvel still faces, such as soil pollution. But it also shows the importance of older trees, their resilience, and their ability to create spaces where life can thrive. Sometimes, what you need to see is already right in front of you — you just have to look closely.

And is your organisation going to become a zoöp now?

That would be fantastic. The Goethe-Institut Niederlande is embedded in a network of 150 institutes across 99 countries, with well over 4000 employees. Even if we were to experiment with the zoöp model locally, we would still be part of that network which, eventually, goes all the way to the German Foreign Office. That poses new and exciting challenges for the model. So, I think we should try it—we can only learn.

To finish, a question again for both of you: What is your favourite scent, please?

Viola: Very controversial, but horse stables. The mixture of horses, hay and leather always brings back nice childhood memories.

Will: My cat Rubicon’s head.