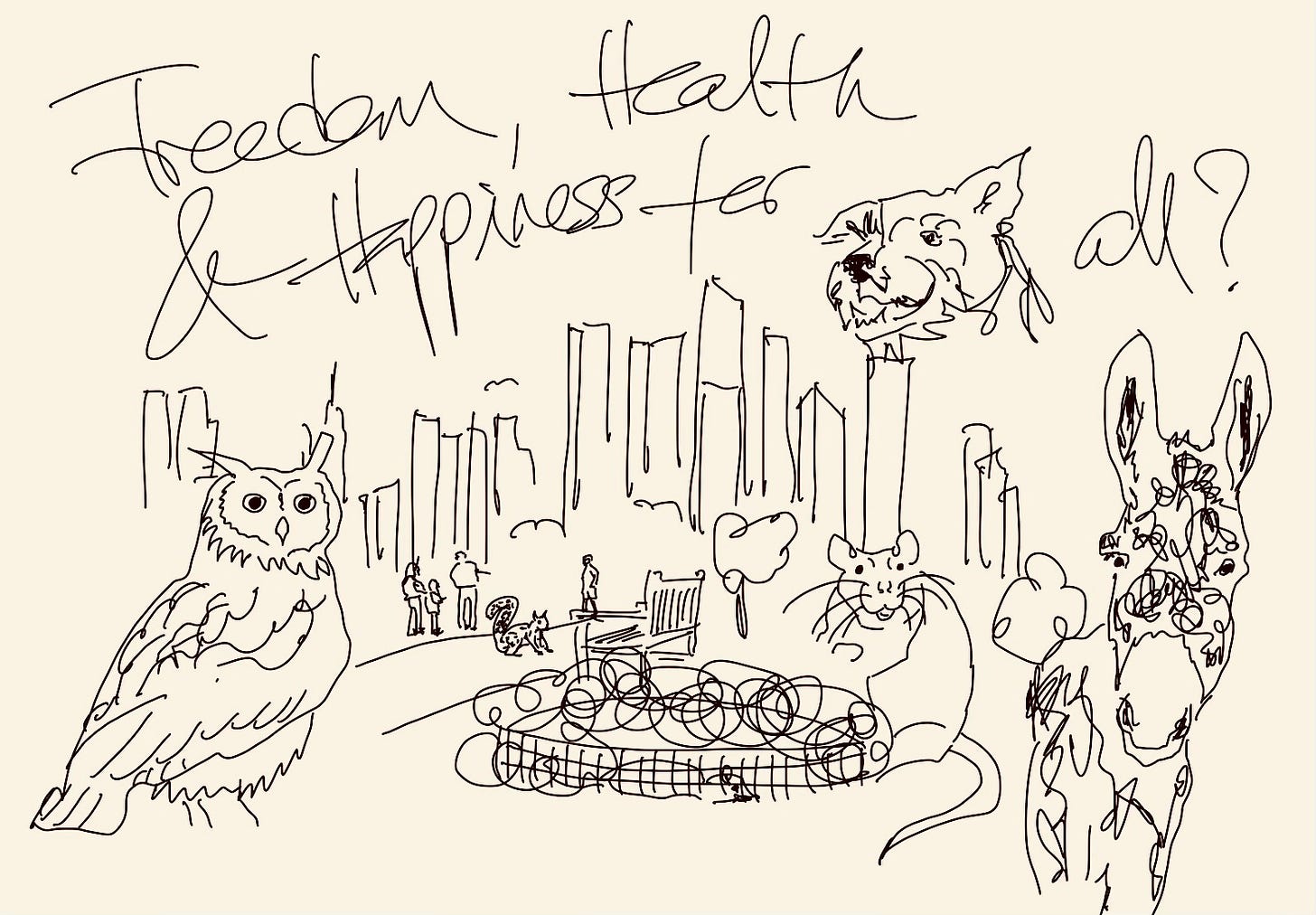

Earlier this month, I gave my talk on “cities as catalysts for improved human-animal relations” online because I could not travel to a conference on utopias and animal ethics in Münster, Germany. I post a summary here. Drop me a question or comment if you like!

Flaco’s Law

I love a good story about animals managing to make space in people’s hearts and minds for themselves. Though Flaco’s story ends with his death, it shows how urban encounters between humans and other, wild living animals can prompt a shift in perspective - in his case, even leading to a new policy to the benefit of yet another species: rats.

Flaco was an Eurasian eagle-owl who hatched in captivity, was exhibited for over a decade in a New York zoo and let loose by humans unauthorised by the zoo in February 2023. We don’t know how Flaco perceived these humans, as liberators or vandals, but he took the chance and explored life in the wild, which, for him, meant the parks of the Big Apple. He taught himself how to hunt in just about ten days and generally to survive in the urban jungle. Most importantly, he landed straight in many people’s hearts.

What stands out to me in the media coverage Flaco received is a visit to writer Nan Knighton and her husband John Breglio who, honoured by having been visited by the owl (whom they considered “bird royalty”), stated:

He brings people together for some reason. Who does it but an animal? You know, an owl, as opposed to politicians or other people.

And bringing people together Flaco did! When he had died after colliding with a building, a good year (!) after his escape, the autopsy showed that, in addition to being afflicted by a pigeon herpes virus, he had remnants of rat poison in his blood. This is a widespread cause of death for urban raptors, but it took Flaco’s fate for the city to decide to do something about it - much to the benefit of rats! As member of New York City Council Shaun Abreu stated:

We can’t poison our way out of this, we can’t kill our way out of this.

So: They started trialling contraception for rats. Compulsory contraception is not morally unproblematic, but it seems significantly better than being killed. These rats, too, are now closer to be seen as sentient individuals whose lives and fates are connected with those of other animals in complicated ways. That is, of course, the reality of life for us and all other animals, just that we rarely make space to consider it.

Perhaps cities, as quintessential human environments, are not where we should expect full-blown utopian experiments, with humans and other animals enjoying the same freedoms and services (as needed). But we can consider them hetero-topias, spaces that follow different rules and norms and allow for transformative experiences and experiments in living. These are unlikely to lead to “simply better”, moral outcomes - after all, letting Flaco loose meant introducing a predator into the urban environment. But perhaps simple moral utopias is just not what anybody needs.

Transcending the human condition

Cities carry utopianism and cultural transformation in their DNA. They are places of dreams and possibility, their link with utopian thinking and projects is ancient. Though primarily designed to shelter humans from “nature”, including predators, other animals were always present in cities. Domesticated animals, for better or worse. But non-domesticated animals, too, played important roles - and we are only just learning to appreciate them.

There are conventional and less conventional ways how wild living animals are co-creators of the urban and not rogue creatures messing with the system. Conventionally, they help with rubbish removal, pollination, seed dispersal, aeration, fertilisation as well as landscaping. Less conventionally, these animals are sources of admiration and inspiration, inspire playful and caring behaviours, and can help with forgetting the heavy or all-too-human stuff of human existence.

For utopian thinking, the less conventional ways are neither trivial nor just a luxury. Admiring beings that lead wild lives, drawing inspiration from them, empathising with them and respecting them are ways of transcending the human condition. We already pay enough attention to getting something from wild animals - think ecosystem “services” - and perhaps putting “a price on nature” in return. Yet that just speaks to a base, mercantilistic layer of the urban condition. Yes, cities have often been market places, but they were hardly ever just that.

Cities can be sanctuaries for wild living animals - whether that is because the urban flora is more varied and appealing for pollinators and birds, because urban humans are more chilled around (some) predators, or because people actively invest in co-creating urban spaces and introduce animals such as beavers or water voles.

A lot remains to be done to create urban cultures that work for all animals, to transcend human perspectives on say traffic and segregation of space. The quintessential urban right to remain anonymous - and just go after one’s business without establishing close social relations - would also stand to benefit other species.

Such transformation of urban spaces is not a task for Flaco et al. alone. Human support is crucial. Perhaps a slightly wilder approach to philosophy that considers the other animals’ perspectives can help.

Animal-informed philosophy

Writing my dissertation in political philosophy on the good city, I was aghast to find what Le Corbusier (of all) had to say about animal perspectives (The City of To-Morrow and Its Planning, p. 5):

Man walks in a straight line because he has a goal and knows where he is going […].The pack-donkey meanders along, meditates a little in his scatter-brained and distracted fashion, he zigzags in order to avoid the larger stones, or to ease the climb, or to gain a little shade; he takes the line of least resistance. But man governs his feelings by his reason […].

Of course, “man” does …

If life, and particularly life with other animals, has taught me anything, then that straight lines never lead from one place to a better one. So: I have modelled an animal-informed philosophy based on what I learned about animal-informed therapy. Unlike animal-assisted therapy, for which you need specially trained and bred animals (again, not morally unproblematic!), animal-informed therapy works with stories and anecdotes people provide about animals they just happen to meet or own.

Anecdotes are great. I feel that philosophers should run wild with them if they do not want to forever hold on to the hem of ethological and animal welfare sciences, which are not without ethical and methodological problems. The animal-informed philosophy I envision allows people to learn from and with other animals through shared experiences. It also allows for collaboration with the arts and various forms of creative research. An example.

Urban Stops for “Philosophy in the Wild”

Again, no straight line can be drawn from me finding out about Mary Midgley while I was still a fresh postdoc in Munich to me now, a good decade later, sending her actual biscuit tin to philosophers, animal studies scholars and artists around the world. But last autumn, I got the opportunity to curate a second round of the global public philosophy project Notes from a Biscuit Tin for Women in Parenthesis and set a different focus: “Philosophy in the Wild”.

I immediately knew that I wanted to focus on what Midgley called the ‘mixed community’. She used the term to stress that humans have never ever lived apart from other animals. Hence humans have a special capacity for understanding many other species’ needs and interests. Indeed, the tools humans have developed to communicate with each other can to some extent aid in communicating with other animals. Of course, we can empathise and communicate to exploit - but we can also do better than that. And many people are already doing it or trying hard.

The project will cover three types of human-animal-relations. I will explain which and why in subsequent posts - and also what role multispecies poetry plays in it. But as far as the urban stops are concerned, I am particularly looking forward to animal-informed notes from three sites:

Bangalore, where we collaborate with the wonderful Sindhoor Pangal, author of Dog Knows, to learn about making space for and with free-roaming dogs.

Vienna, where we collaborate with the bright Konstantin Deininger, freshly minted postdoc, and brilliant Claudia Towne Hirtenfelder, founder, producer and host of The Animal Turn, to learn about both what has happened to Vienna’s wildlife hospital and work on behalf of and with urban bats.

Amsterdam, where we collaborate with the Goethe Institute’s very own Viola Karsten who is orchestrating an exciting institutional learning experience around the Zoöp idea - an idea that sounds straight out of Midgley’s cookbook. Great minds think alike.

And even greater minds like to think with other animals - and not just about them.

Great story about Flaco! Yes, anecdotes can shed light that open our eyes to new appreciation of our living community. Another New York City example of an animal that turned urban dwellers toward mindfully seeing animals right around them, even in the city, was "Pale Male" a red-tailed hawk who lived in Central Park for 13 years. A story of survival and love in the "Big Apple." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pale_Male.